National Visionaries and Texas Pioneers Who Built Economic Power

Introduction

Black American business history is often framed narrowly—either as isolated success stories or as footnotes to broader civil rights narratives. In reality, Black entrepreneurs were builders of systems: banks, supply chains, manufacturing firms, retail ecosystems, and civic institutions that predated modern conversations about economic inclusion.

This article brings together two perspectives:

- Five lesser-known national Black business history stories that shaped American capitalism

- A Dallas–Texas–focused follow-up highlighting regional Black business pioneers whose impact still shapes North Texas today

Together, they offer a more complete picture of Black enterprise as strategy, infrastructure, and legacy—not anomaly.

Part I — Five Little-Known National Black Business History Stories

Robert Reed Church Sr. — From Slavery to Southern Banking Power

Robert Reed Church Sr. was born enslaved in 1839 and became one of the wealthiest Black Americans of the 19th century. After surviving the Memphis Massacre of 1866, he invested heavily in real estate and founded Solvent Savings Bank, one of the first Black-owned banks in the South.

Why this matters:

Church viewed capital access as a civil rights strategy. His banking and real estate investments stabilized Black commercial districts and created durable economic infrastructure—not just individual wealth.

Maggie Lena Walker — America’s First Female Bank President

In 1903, Maggie Lena Walker founded and led St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, becoming the first woman of any race to charter and run a U.S. bank.

Why this matters:

Walker built a vertically integrated economic system—banking, insurance, publishing, and retail—anticipating modern fintech and community banking models by over a century.

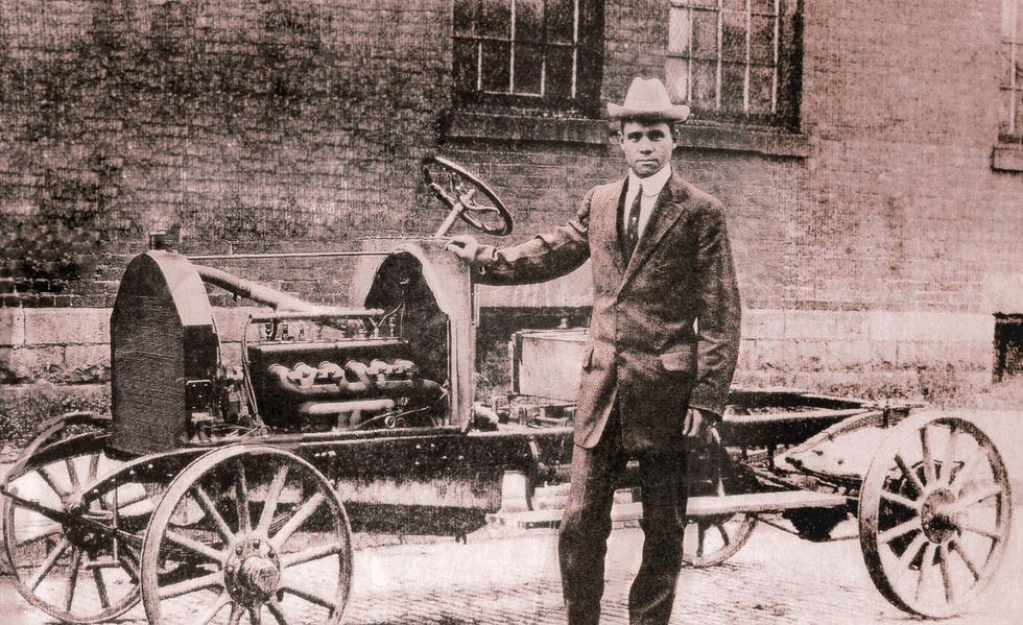

C.R. Patterson — America’s First Black-Owned Auto Manufacturer

C.R. Patterson founded C.R. Patterson & Sons, producing luxury automobiles and commercial vehicles before Ford became dominant. From Britannica.com: “Black-owned and operated carriage, automobile, and bus manufacturing and repair company based in Greenfield, Ohio, from 1873 to 1939. The company is notable for having been the only automobile company in the United States, as of the early 21st century, to be entirely Black-owned.”

Why this matters:

Patterson’s story disrupts the myth that Black entrepreneurs were absent from early industrial America. His company fell not from lack of innovation, but from aggressive consolidation by larger manufacturers.

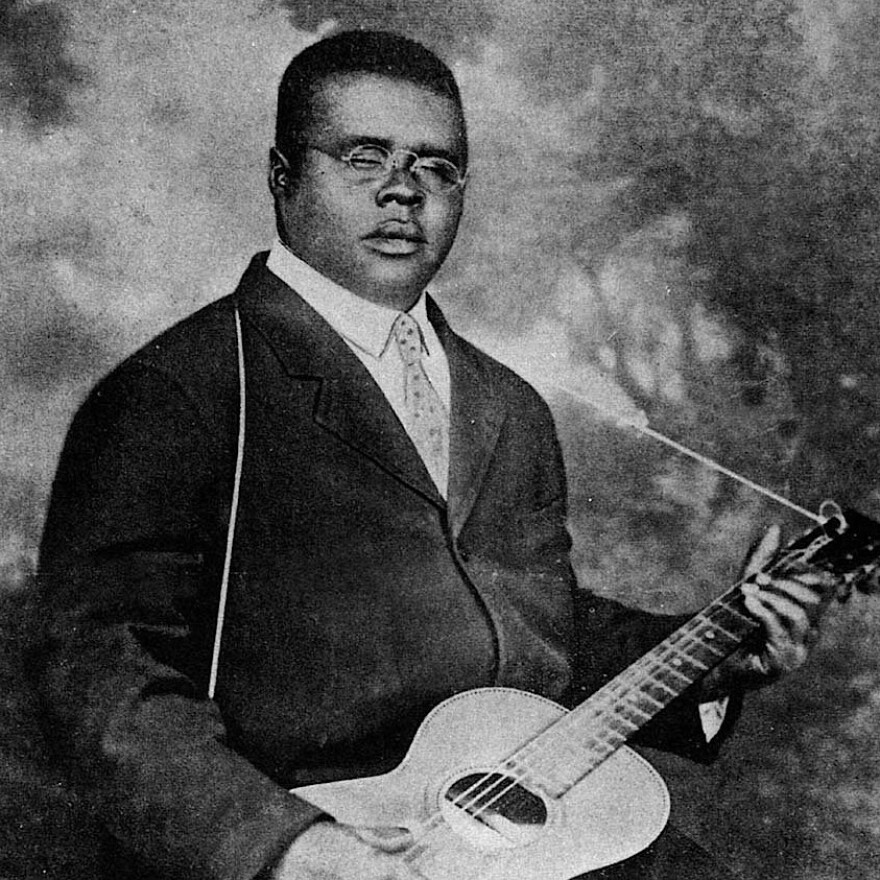

Annie Turnbo Malone — The Architect Behind the Beauty Empire

Before Madam C.J. Walker, Annie Turnbo Malone built the Poro Company, employing tens of thousands of Black women globally through a franchise-like sales and training model.

Why this matters:

Malone pioneered workforce development, global distribution, and brand training ecosystems—long before these became standard corporate practices.

Homer Plessy — When Business Economics Shaped Civil Rights Law

Homer Plessy is remembered for Plessy v. Ferguson, but the case also reflected business incentives. Railroads supported segregation to reduce operational complexity and cost.

Why this matters:

The case illustrates a recurring American pattern: business efficiency arguments influencing public policy—seen today in housing, healthcare, and technology regulation.

Part II — Dallas & Texas Black Business Pioneers

Dallas had a Freedman’s Town, located north of downtown in what later became parts of Uptown and North Dallas.

Freedman’s Town developed in the late 19th century as a residential and commercial center for formerly enslaved people and their descendants.

Business and economic significance:

- Skilled Black laborers, tradesmen, and service providers

- Early Black-owned boarding houses, shops, and service firms

- A foundational population that later fed into Deep Ellum and South Dallas commerce

Why this matters:

Much of Dallas’ early Black economic activity was later displaced and erased by urban expansion. The land appreciated; ownership did not transfer with it. This pattern still echoes in modern redevelopment debates.

And then Freedmen’s Town in Houston was established in the late 1860s by formerly enslaved African Americans in Houston’s Fourth Ward. It was not founded by a single individual, but collectively built through land acquisition, mutual aid, churches, and Black-owned trades.

Business and economic significance:

- Black-owned construction, carpentry, and brickmaking enterprises

- Churches that doubled as financial and organizing centers

- Homeownership as a primary wealth strategy

- One of the earliest examples of Black urban land control in Texas

Why this matters:

Freedmen’s Town functioned as a self-governing economic zone during segregation, proving that Black Texans were not merely participants in markets, but designers of economic ecosystems.

A. Maceo Smith — Architect of Black Economic Power in Dallas

A. Maceo Smith was a businessman and strategist who leveraged commerce, political organization, and labor coordination to expand Black economic influence in Dallas.

Why this matters:

Smith understood that political rights followed economic leverage. His work integrated business ownership, civic pressure, and coalition-building—principles still relevant for modern urban development.

The Knights of Pythias Temple — Dallas’ Black Business Nerve Center

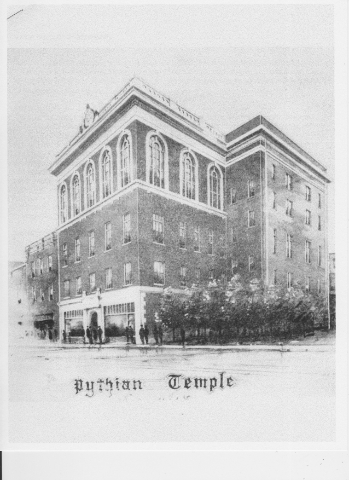

The Knights of Pythias Temple on Elm Street housed Black-owned banks, law offices, doctors, and retailers during segregation. From CandysDirt.com: “William Sydney Pittman, the first African American architect in Texas, designed the Knights of Pythias building shortly after moving to Texas in 1912 to pursue work.

Built in 1916 on Elm Street in Deep Ellum, the Knights of Pythias Temple served as one of the most important Black-owned commercial and professional hubs in Dallas during segregation. The building housed Black-owned banks, law offices, medical practices, insurance firms, and civic organizations—functioning as a self-contained economic ecosystem when access to white institutions was restricted.

After opening, the five-story Knights of Pythias building quickly became an important landmark in Deep Ellum. Pittman graduated from Tuskegee Institute and then Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, completing studies in architectural drawing and structural work. At Tuskegee, he met Booker T. Washington, who recognized and encouraged his architectural talents. Pittman went on to marry Washington’s daughter Portia in 1907… Due to the significance of the building architecturally and to the African American history of Dallas, the City of Dallas designated it a Landmark in 1989 to protect it in perpetuity..”

Adaptive Reuse and Restoration

Years later, In the late 2010s, the historic structure was restored and adaptively reused as part of the Kimpton Pittman Hotel, operated by Kimpton Hotels & Restaurant Group. The redevelopment preserved the original Beaux-Arts façade and significant interior spaces, including the grand ballroom, integrating them into a modern hospitality experience.

Why This Matters

The Pittman restoration represents a rare case where a historically Black business landmark was not erased, but structurally preserved within a new economic model. It highlights a central tension in modern urban redevelopment:

- Preservation vs. displacement

- Historical recognition vs. ownership continuity

- Cultural memory embedded in profitable real estate

For Dallas, the building stands as a physical reminder that Deep Ellum’s cultural reputation was originally built on Black-owned economic infrastructure—not just music and nightlife.

Editorial note for ABoD: This site offers an opportunity to move beyond nostalgia and ask harder questions about how Black business legacy is acknowledged, capitalized, and carried forward in today’s high-growth corridors.

Why this matters:

This was Dallas’ version of “Black Wall Street”—a multi-tenant business hub that enabled professional services, capital circulation, and community resilience under exclusionary laws.

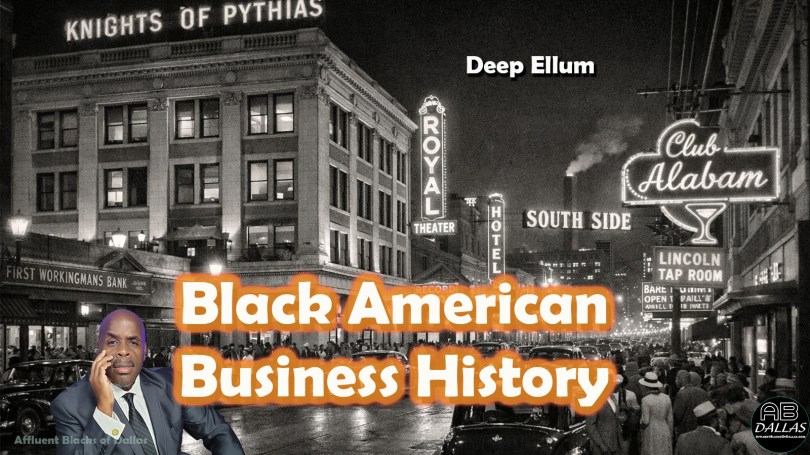

Deep Ellum — More Than Music

Before gentrification, Deep Ellum was a dense Black commercial zone—printing presses, insurance offices, restaurants, and performance venues operating as a unified economic district.

Why this matters:

Deep Ellum demonstrates how culture, commerce, and real estate appreciation were historically linked—often before displacement erased original ownership.

South Dallas Entrepreneurs — The Quiet Continuity

South Dallas sustained Black-owned businesses for decades—grocery stores, funeral homes, trades, and service firms—providing economic continuity even as capital fled other neighborhoods.

Why this matters:

Not all Black business history is dramatic. Much of it is quiet resilience: businesses that survived multiple economic cycles without headlines but with lasting impact.

Closing Reflection for ABoD Readers

To be sure, Black American business history is not a sidebar to American capitalism: it is a parallel foundation. From national banking pioneers to Dallas-based system builders, these entrepreneurs understood something timeless:

Ownership creates leverage. Infrastructure creates longevity. Culture alone is not enough.

For Affluent Blacks of Dallas, this history is both retrospective and instructional. It informs how wealth, influence, and civic presence can be built intentionally in today’s North Texas landscape.